Organoids

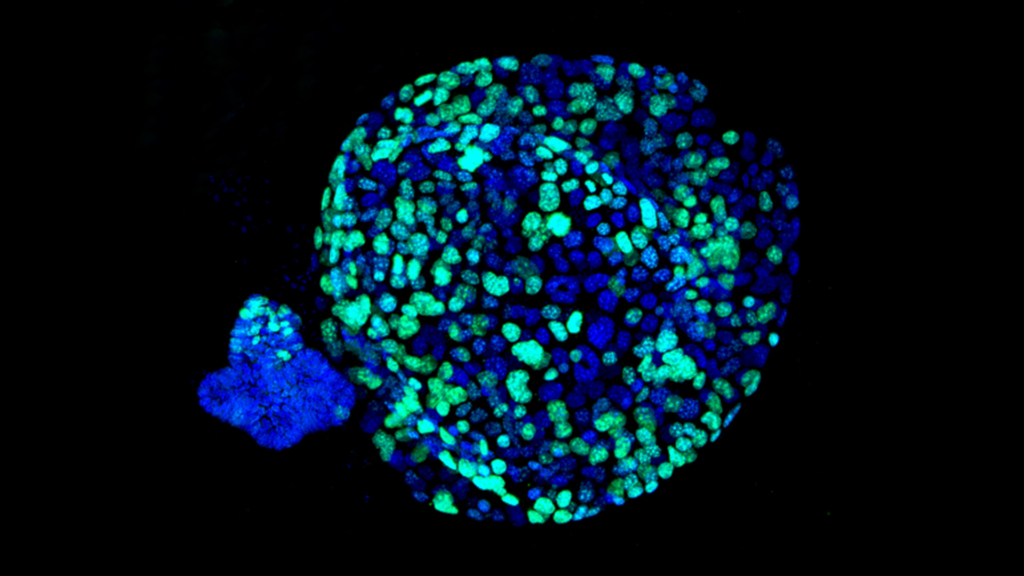

Developed by our Chief Scientist David Tuveson, M.D., Ph.D., and his collaborator Hans Clevers, M.D., Ph.D., president of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, organoids are microscopic “copies” of an individual patient’s tumor, grown from samples of pancreatic tissue. Organoids have been successfully studied for other cancers and used to help predict the best potential treatments for a cancer patient. Under Dr. Tuveson’s leadership, scientists at our dedicated laboratory at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory are spearheading the use of organoids in pancreatic cancer.

Organoids enable researchers to observe pancreatic cancer from its beginning and repeatedly test new diagnostics and therapies in the lab. The development of this system was a monumental step forward in pancreatic cancer research because it brings the laboratory closer to the clinic.

In our research project, a patient’s organoid is genetically sequenced and its genetic makeup is characterized. It is then treated with many compounds and combinations of compounds to determine which are most effective in killing the cancer cells. This process is the essence of personalized medicine, where the precise treatment for each patient is selected based on the makeup of his or her tumor. In fact, researchers recently demonstrated that organoids can quickly and accurately predict how patients with pancreatic cancer will respond to a variety of treatments.

“When we think about how we can take better care of patients, we have to think and act differently. Organoids act as a telescope into pancreas cancer, so we can see it, watch it respond in a dish. That provides a level of insight we’ve not had before and may allow doctors to predict and prescribe the best medicine for individual patients.”

– David Tuveson, M.D., Ph.D.

mRNA acts as a messenger carrying instructions from DNA for controlling the synthesis of proteins. The team assessed these mRNA levels in individual organoids to determine gene signatures that predict sensitivity to the five standard chemotherapies administered to pancreatic cancer patients. Three of these signatures correctly identified large numbers of patients who had responded to these drugs, and showed that those responding patients lived much longer before the cancer progressed. The signatures should enable physicians to choose the correct chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer patients for first-line treatment.

Researchers demonstrated this method provides an effective precision-medicine “pharmacotyping” (drug-testing) pipeline. To do so, the organoid from the patient’s cancer was cultured, and then used to test all possible standard-of-care chemotherapy drugs. Scientists found many of the organoids that did not respond well to chemotherapy were responsive to a variety of investigational drugs based on the gene signatures that occur as a result of tumor development.

Dr. Tuveson and his team plan to further refine the gene signatures through additional experiments, then test the genes’ ability to predict treatment sensitivity in clinical trials. In fact, Brian Wolpin, M.D., MPH, director of the Hale Center for Pancreatic Cancer Research and the Gastrointestinal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, is in the early stages of applying the organoid technology on patients.

The organoid research study was published in the May 31, 2018 edition of Cancer Discovery.

The organoid research is funded in part through a grant from the Gail V. Coleman and Kenneth M. Bruntel Organoids for Personalized Therapy Project.